On 25 September 1957, U.S. civil rights activists won the right for African American children to go to the same schools as white children at Little Rock, Arkansas. But 60 years on, many schools in the U.S.A. are still separated along color lines. And one of the most segregated school systems in the country is not in the South, it’s New York City.

September 25 2017 marks 60 years since the "Little Rock Nine", a group of African American students managed to gain access to the all-white Central High School in Arkansas. It should be a joyful anniversary, marking the beginning of the end of the iniquitous system that separated white and black children into different schools, and generally reserved the lion's share of resources for the white students.

Click here for a timeline of school integration at Little Rock.

Click here for a timeline of school integration at Little Rock.

Happy Ending?

It would be nice to think that Little Rock marked the beginning of a new, more equal, integrated era for U.S. education. After all, there are plenty of examples of African Americans who have been able to access the country’s top educational establishments - one of them became President.

But research shows that overall the school system is still highly divided along class and economic lines. And even today those often correspond to skin colour.

New York City is one of the most diverse places in the U.S.A. Its population includes people from almost every country in the world. Yet a 2014 study* by UCLA’s Civil Rights Project found that the city's schools, and those in the wider New York state, were far from being models of integration:

“Nearly half of public school students in New York [state] were low-income in 2010, but the typical white student attended school where less than 30% of classmates were low income. Conversely, the typical black or Latino student attended a school where close to 70% of classmates were low-income.”

The New York City School District is the biggest in the country, serving a little over a million students from Kindergarten to High School. The New York Times recently calculated that black and Hispanic students in the city, on average, attend schools where the student body is 80 percent black or Hispanic.

By the city’s schools department’s own admission, “30.7% of our schools are racially representative today.” In other words, 70% of schools don’t reflect the population of the city.

No one is accusing New York of actually pursuing segregation policies. Particularly for younger students, the racial mix in their schools is representative of that in the neighbourhoods they serve. Since the residential areas tend to have a majority population of a specific background, the schools that serve them do too. High-school admissions should theoretically be more mixed as parents have the right to request any school in the city. But the application process is complicated and families who themselves are college educated and have no language barriers find it easier to navigate and get their children places in the most prestigious schools.

In June 2017, the NYC Schools Department published a new policy document “Equity and Excellence for All: Diversity in New York City Public Schools”, recognising the problem and outlining action it plans to take to remedy it. It promises to, “Increase the number of students in a racially representative school by 50,000 over the next five years.” 50,000 out of a million doesn’t seem an especially ambitious goal.

The Bigger Picture

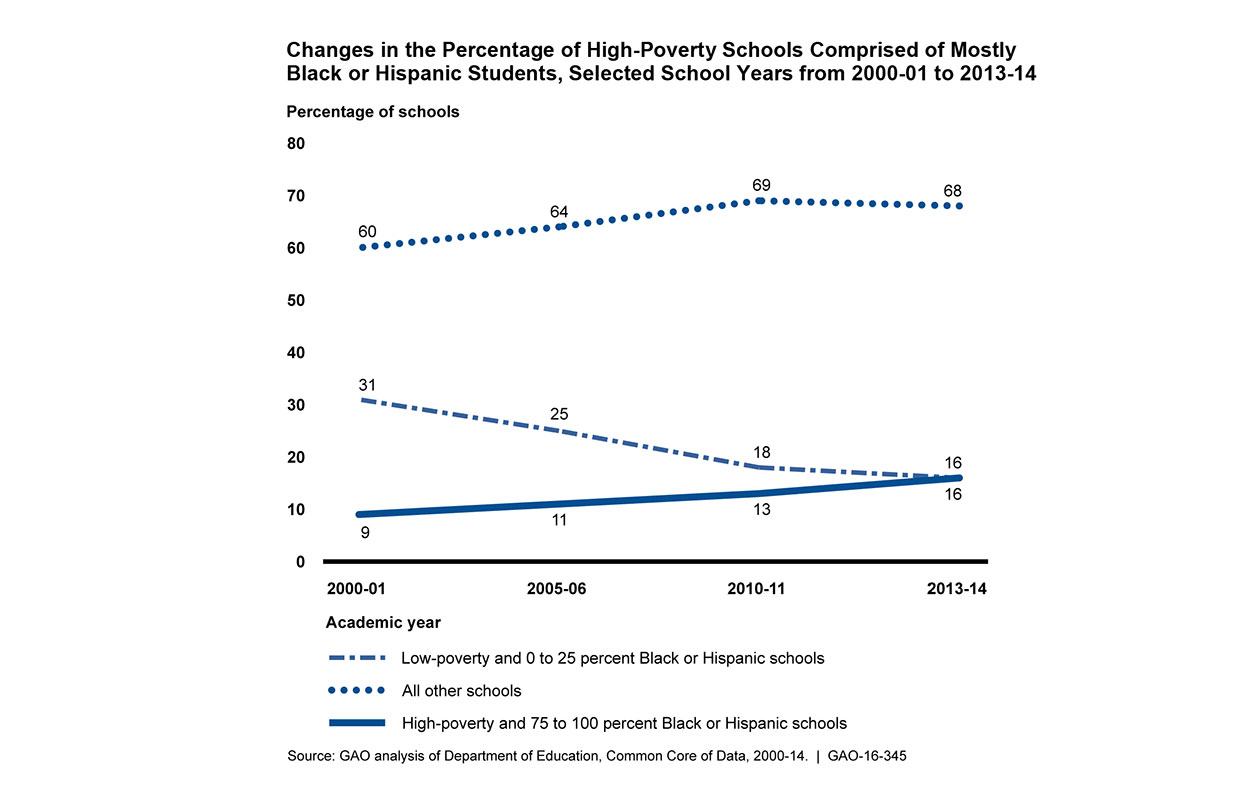

However, New York’s situation is part of a national trend. In 2016, the Government Accountability Office issued a report which had been requested by Democratic Representatives. Analysing federal Department of Education data, it concluded that nationally the percentage of, “public schools that had high percentages of poor and Black or Hispanic students grew from 9 to 16 percent between 2000 and 2014, These schools were the most racially and economically concentrated: 75 to 100 percent of the students were Black or Hispanic and eligible for free or reduced-price lunch,” a generally accepted indicator of poverty. And these poor schools systematically offer fewer educational opportunities to their students, trapping them in a cycle of poverty and educational underachievement.

In some places the increasing segregation is an effect of demographics – children of parents who had few educational opportunities themselves and so few higher-income job opportunities in turn find themselves in under-resourced schools. The de facto segregation isn’t part of a policy, but it would require a specific policy of integration to reverse it.

But in other areas, resegregation is a deliberate policy. In the Southern states, school desegregation was often enforced by court order in the 1960s. By the 1990s many states applied to have the orders revoked, because, they said, they were no longer necessary. Desegregation had been achieved. Non-profit news site ProPublica found in a 2014 report that in 1972, under desegregation orders, “Only about 25 percent of black students in the South attended intensely segregated schools in which at least nine out of 10 students were racial minorities.” Where desegregation orders were revoked between 1990 and 2011, “53 percent of black students now attend such schools.”

The color barriers are re-erected bit by bit. Parents’ groups or political groups fight to redraw the borders of school districts to limit them to communities with mainly white residents, so that their schools in turn become mainly white.

Some districts, such as Cleveland, Mississippi, on the other hand, simply ignored Brown v. Board of Education. In 2016, a federal court finally ordered the school district to desegregate its schools, 62 years after the Supreme Court decision.

*"New York State’s Extreme School Segregation" by John Kucsera with Gary Orfield. University of California, Los Angeles

Copyright(s) :

National Park Service

Library of Congress

NYC Schools Department

GAO

> Little Rock School Integration, 1957

> Montgomery Bus Boycott: A Victory for Civil Rights

> Little Rock School Integration Videos

> African American History on the Web

> Martin Luther King Day on the Web

> Civil Rights: The Montgomery Bus Boycott

Tag(s) : "anniversary" "civil rights" "equality" "Little Rock" "NAACP" "New York" "schools" "Segregation" "Supreme Court" "U.S. history"