Jamaica is famous for reggae, and in particular Bob Marley. But Jamaican music has a long and complex history, and is much more influential than seems credible for a nation with a population of less than 3 million. In music, as in athletics, Jamaica punches well above its weight. An exhibition at the Philharmonie demonstrates how music participated in, and was influenced by, the struggle against slavery and oppression.

Like most of the Caribbean islands, European contact with Jamaica was synonymous with slavery. When Christopher Columbus claimed the island for Spain in 1494, the Spanish enslaved the local people of the Arawak or Taino tribe. Mistreatment, and exposure to European diseases, decimated the population. By the time the British fought the Spanish for control of Jamaica in 1655, the indigenous population had been wiped out.

As elsewhere in the Americas, the British established sugar and tobacco plantations. These labour-intensive commodities were only profitable thanks to the free labour provided by slaves transported to the Caribbean from Africa. Until the abolition of the slave trade in 1807, it is believed that a million slaves were transported to Jamaica. When slavery itself was abolished in 1834, slaves outnumbered the white population by 15 to one.

Revolt

During the period of slavery, there had been regular slave revolts. The end of slavery didn't suddenly improve life for the former slaves. The white population still had financial and political control. But the black population strove to conquer oppression, by subversion if not by outright rebellion.

Mento music developed in the nineteenth century as a way of poking fun at the ruling class, and making political statements. Musically, if was a creole, combining West African song and dance with European dance forms such as the quadrille. Like its close cousin calypso from the neighbouring Trinidad and Tobago, mento performers competed to find the most biting, outrageous lyrics.

The Sound of Freedom

Mento reached its height of popularity in the 1950s, but as Jamaica approached independence in 1962, a new sound took over – ska was carefree, danceable and largely lyric-free. It is intimately linked with a uniquely Jamaican phenomenon, the sound system.

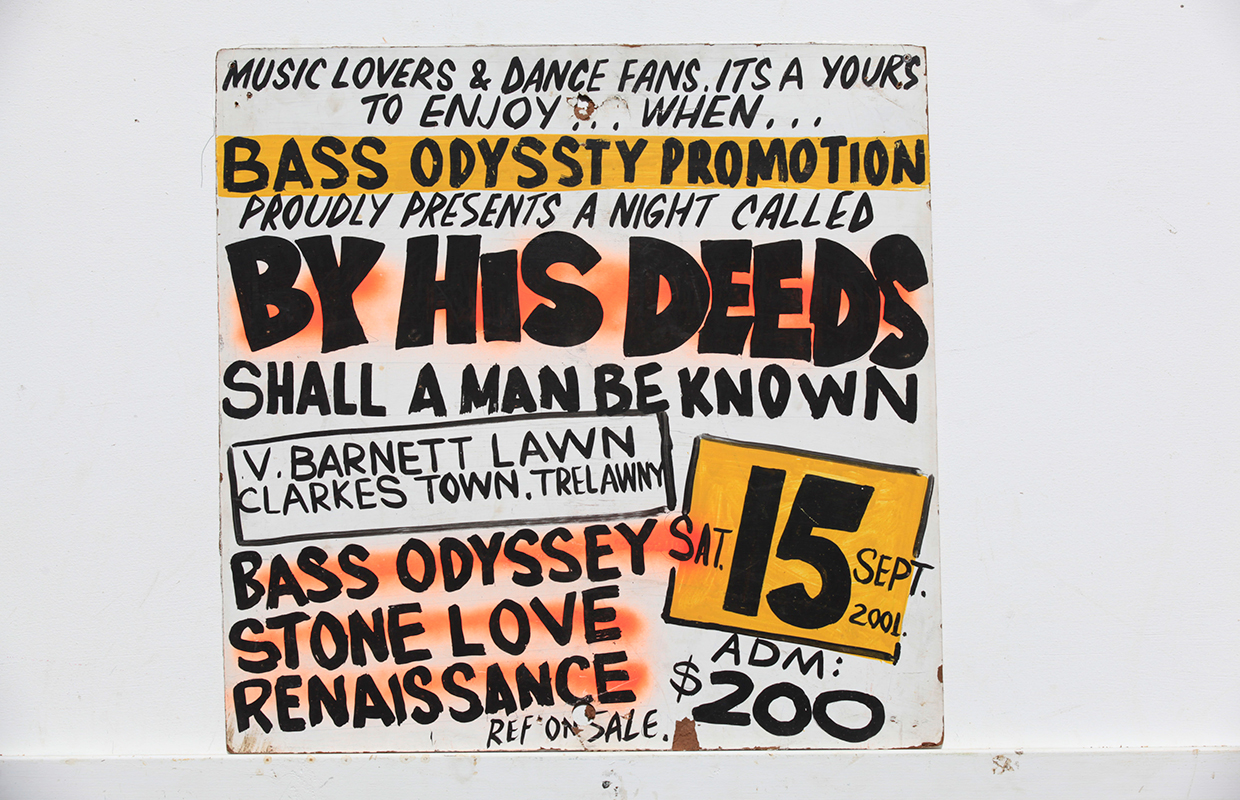

In the 1950s, Jamaican national — colonial — radio, didn't play either mento or jazz and R'n'B that were becoming increasingly popular. So enterprising businessmen set up mobile, outdoor discos where people could listen and dance to the music they wanted. These became so popular that the rival sound systems came up with inventive ways to attract the most listeners. The number of decibels produced by gigantic amps was one feature, as were colourful handpainted advertising posters. Sound systems and DJs had to have a unique edge and so music studios sprang up making exclusive tracks and special remixes. Later on, DJs started "toasting" – speaking or chanting over tracks, which evolved into rap.

Rastafarians and Reggae

Rastafarians and Reggae

In the late Sixties, when it was becoming clear that post-independence Jamaica was weighed down with debt and poverty, rebellious lyrics again moved to the fore in yet another innovative Jamaican music style: reggae.

Jamaican-born Marcus Garvey was a prominent advocate of the Pan-African movement encouraging a return of former slaves from different colonies to Africa. It encouraged pride in African culture and Jamaica was the birthplace of a uniquely Pan-African religion or spiritual movement, Rastafari, which recognised the emperor of Ethiopia, Haile Selassie (1892-1975), as a living god. Rastifarians believe in a return to Africa, are vegetarians and don't cut their hair, so it forms distinctive dreadlocks.

The most influential proponent of Rastifarianism, was Bob Marley, whose songs are full of Rasta symbols. "War" is an almost verbatim rendition of a speech Haile Selassie made to the League of Nations after Mussolini's Italy invaded Ethiopia.

Marley made reggae and Rastafari famous the world over. The first pop superstar from a developing country, he sang about oppression and Trenchtown ghetto where he spent his teenage years. Bob Marley and his band The Wailers had been making music in Jamaica since the early 1960s. But in 1975 their album Natty Dread became a worldwide hit. Young people around the world adorned their walls with posters of the dreadlocked singer and sang along to anthems like "Trenchtown", "No Woman No Cry" and "Get Up Stand Up", all with their infectious reggae rhythm.

Marley died of cancer in 1981 at the age of 36. But his music remains just as influential today. Exodus (1977) was named Album of the Century by Time Magazine and his song “One Love” was chosen as Song of the Millennium by the BBC.

Jamaica! Jamaica!

The music of Jamaica has a fascinating story to tell. Find out more at the Jamaica! Jamaica! exhibition at the Philharmonie in Paris till 13 August 2017.

There is quite a lot of information on the exhibition site, and a webradio for musical accompaniment — including a playlist by sprinter Usain Bolt. What does the fastest man in the world have in his earphones? Tune in to find out!

Don't miss our B1 Ready to Use Resource about Jamaican music.

Copyright(s) :

Images courtesy Philharmonie de Paris

Mural: Danny Coxson street art in Kingston. © Seb Carayol. Danny Coxson produced original work to give the Paris exhibition a Kingston feel.

Sound System poster: Maxine Walters Collection

Bob Marley: ©Adrian Boot_Urban Image

Tag(s) : "Bob Marley" "exhibition" "Give Me Five 3e" "Jamaica" "L'idée de progrès" "music" "rebellion" "slavery"